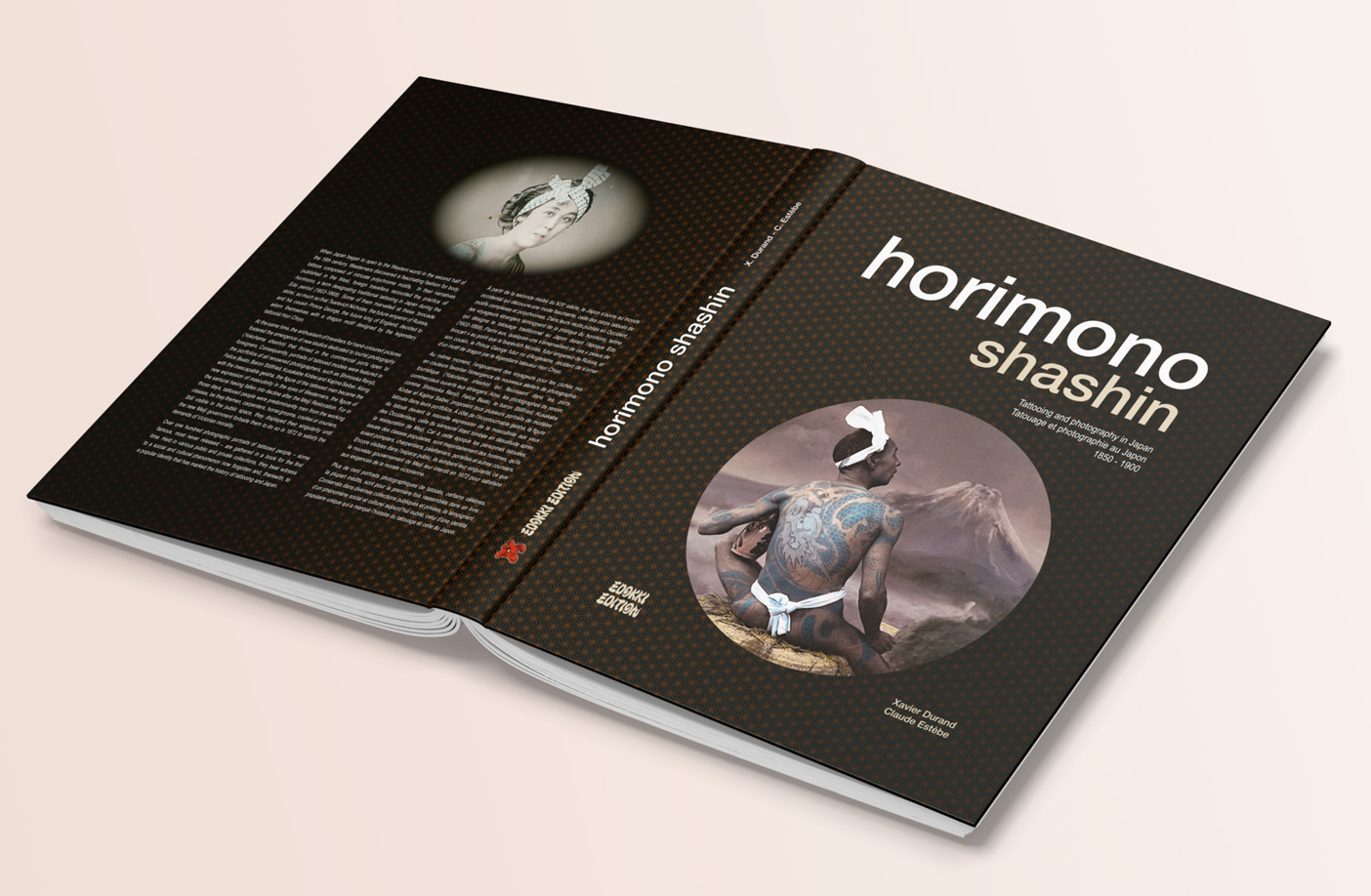

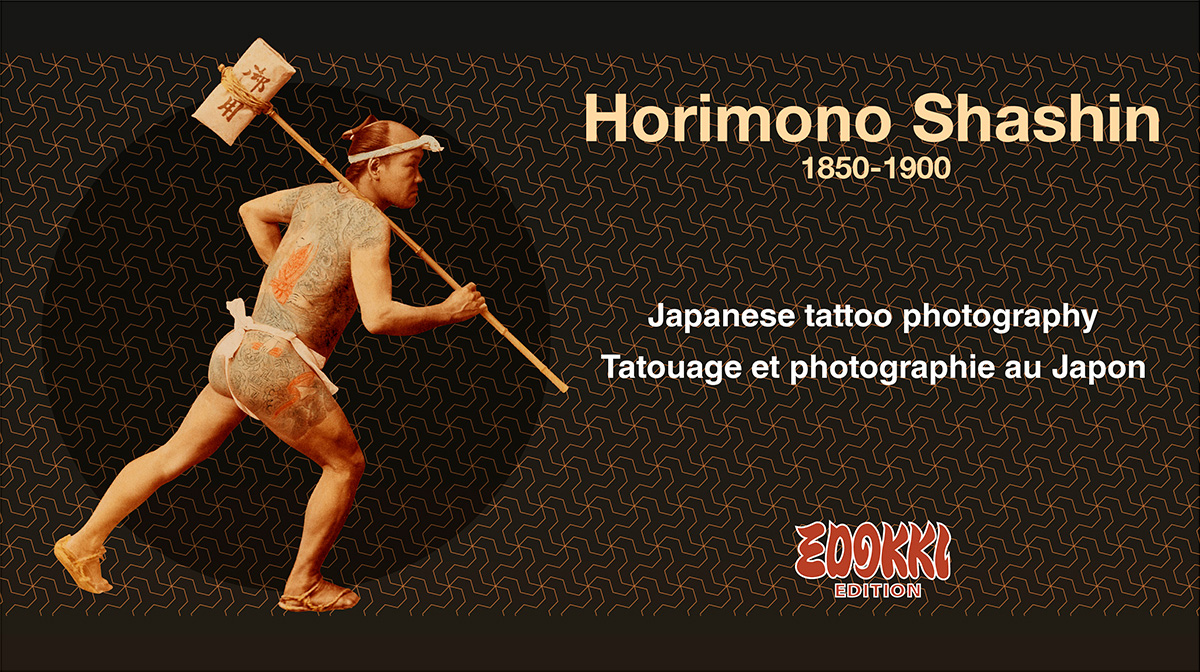

• Horimono Shashin is the first book dedicated to photographs showing tattooing from the second half of the 19th century in Japan

• Horimono Shashin est le premier livre consacré aux photographies montrant le tatouage de la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle au Japon

• 100 original albumen prints mainly from the authors’ collection

• 100 tirages albuminés originaux provenant principalement de la collection des auteurs

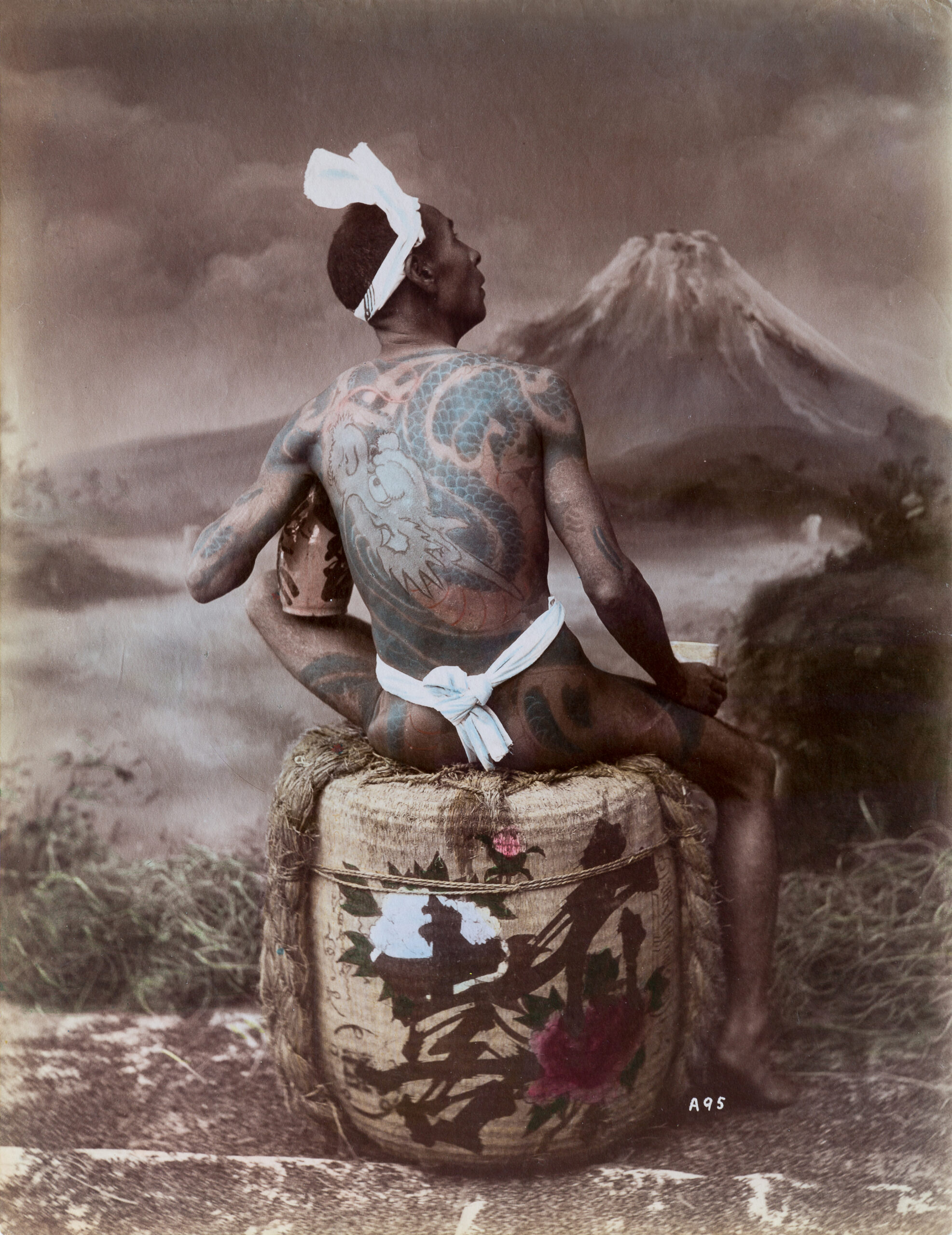

À partir de la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle, le Japon s’ouvre au monde occidental qui découvre une mode fascinante, celle des Japonais tatoués de motifs complexes et polychromes. La pratique du horimono, terme qui désigne le tatouage traditionnel au Japon durant l’époque Edo (1603-1868), est abondamment relatée dans les récits des voyageurs étrangers. Elle est aussi immortalisée grâce à l’engouement des Occidentaux pour les photographies mises en couleurs (Yokohama shashin).

À côté de l’incontournable geisha, la figure du tatoué devient la nouvelle expression de la masculinité, celle du samouraï étant tombée en désuétude après la restauration Meiji (1868). Conservées dans diverses collections publiques et privées, plus de cent de ces photographies de tatoués ont été réunies pour la première fois. Certaines célèbres, la plupart inédite, elles n’ont jamais été ni étudiées ni publiées. C’est l’objet de ce livre qui a besoin de votre aide pour devenir réalité… Un document unique sur la culture du tatouage japonais.

From the second half of the 19th century, Japan opened up to the Western world, which discovered a fascinating fashion: Japanese people tattooed with complex, polychrome designs. The practice of horimono, the term used to describe traditional tattooing in Japan during the Edo period (1603-1868), was widely reported in the accounts of foreign travellers. It was also immortalised thanks to the Western craze for colour photographs (Yokohama shashin).

Alongside the geisha, the tattooed figure became the new expression of masculinity, the samurai having fallen into disuse after the Meiji Restoration (1868). Held in various public and private collections, over a hundred of these photographs of tattooed men have been brought together for the first time. Some famous, most unpublished, they have never been studied or published. That’s the purpose of this book, which needs your help to become a reality… A unique document on Japanese tattoo culture.

Le livre

C’est en 2020 que nous avons décidé d’unir nos compétences pour entreprendre ce projet. Nous avons effectué des recherches aux quatre coins du monde pour localiser et rassembler ces photographies oubliées.

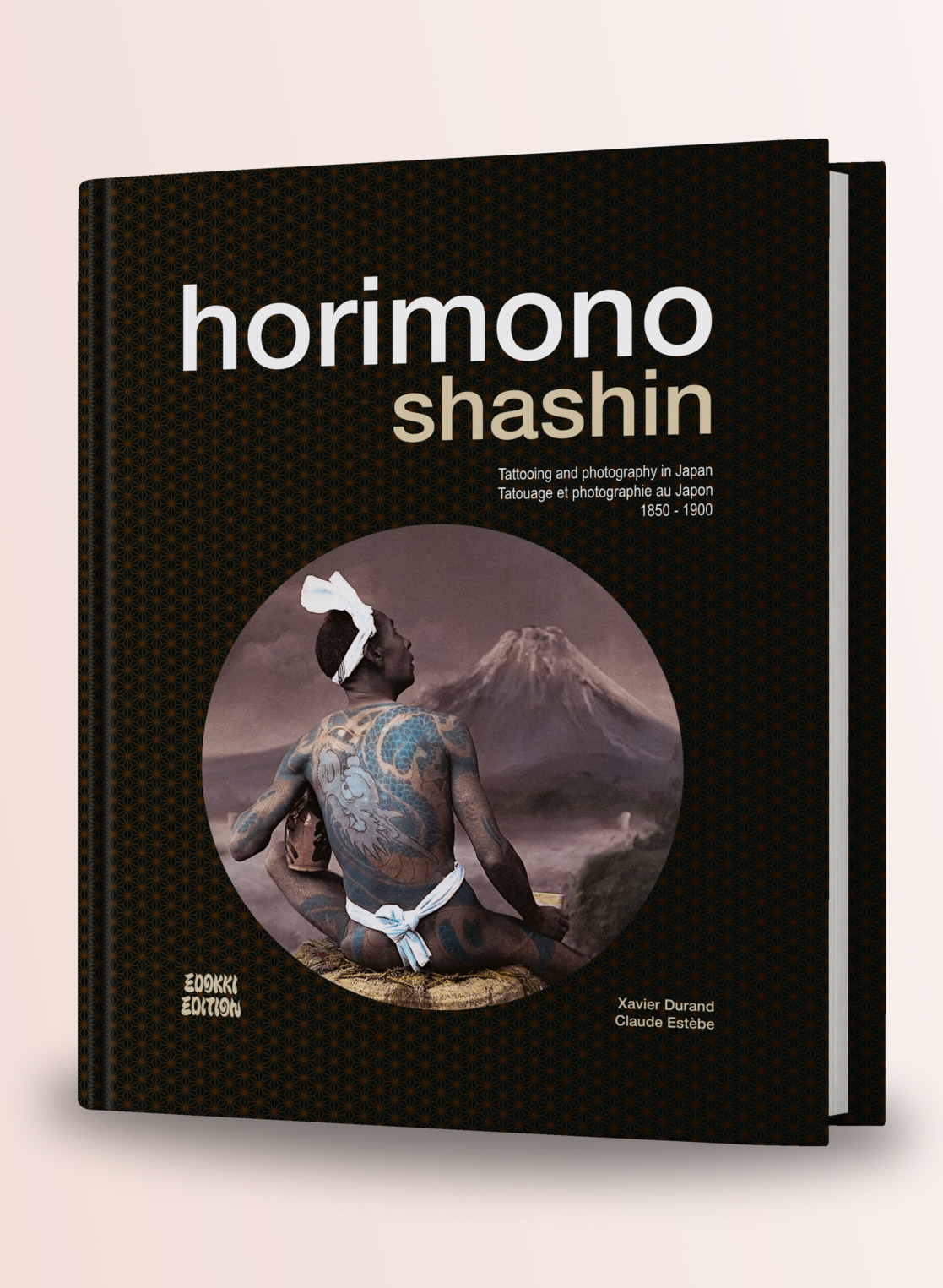

Intitulé Horimono Shashin, le livre reproduira plus de 100 photographies avec une majorité d’épreuves sur papier albuminé coloriées à la main et quelques rares plaques de verre pour lanterne magique. Un travail de restauration de chaque image permettra de restituer le maximum de détails de ces personnes tatouées il y a plus de 150 ans. Les couleurs et le contraste original seront respectées (ce qui n’est souvent pas le cas dans les banques d’images). Les textes seront en anglais et en français, la traduction en anglais sera confiée à Didier Mayhew photographe franco-britannique passionné de sociologie.

La couverture aura des finitions soignées (effet softtouch et vernis sélectif) au format 21,5 x 26 cm, le livre comportera 192 pages intérieures sur un papier de qualité supérieure (170 gr.) avec tranchefile et signet. L’impression se fera courant octobre, les envois se feront à partir de mi-novembre 2024.

Le contenu

La signature en 1858 des traités de paix, d’amitié et de commerce avec les grandes puissances occidentales provoque l’ouverture de l’Archipel. Dès le début des années 1860, Yokohama devient le principal comptoir commercial où se côtoient les nations américaine, britannique, hollandaise, russe et française, habilitées par le régime shogunal. Situé à proximité d’Edo encore fermée aux étrangers, ce port voit les premiers voyageurs s’enthousiasmer pour l’exotisme que leur suggère le Japon d’alors, le tatouage en fait partie.

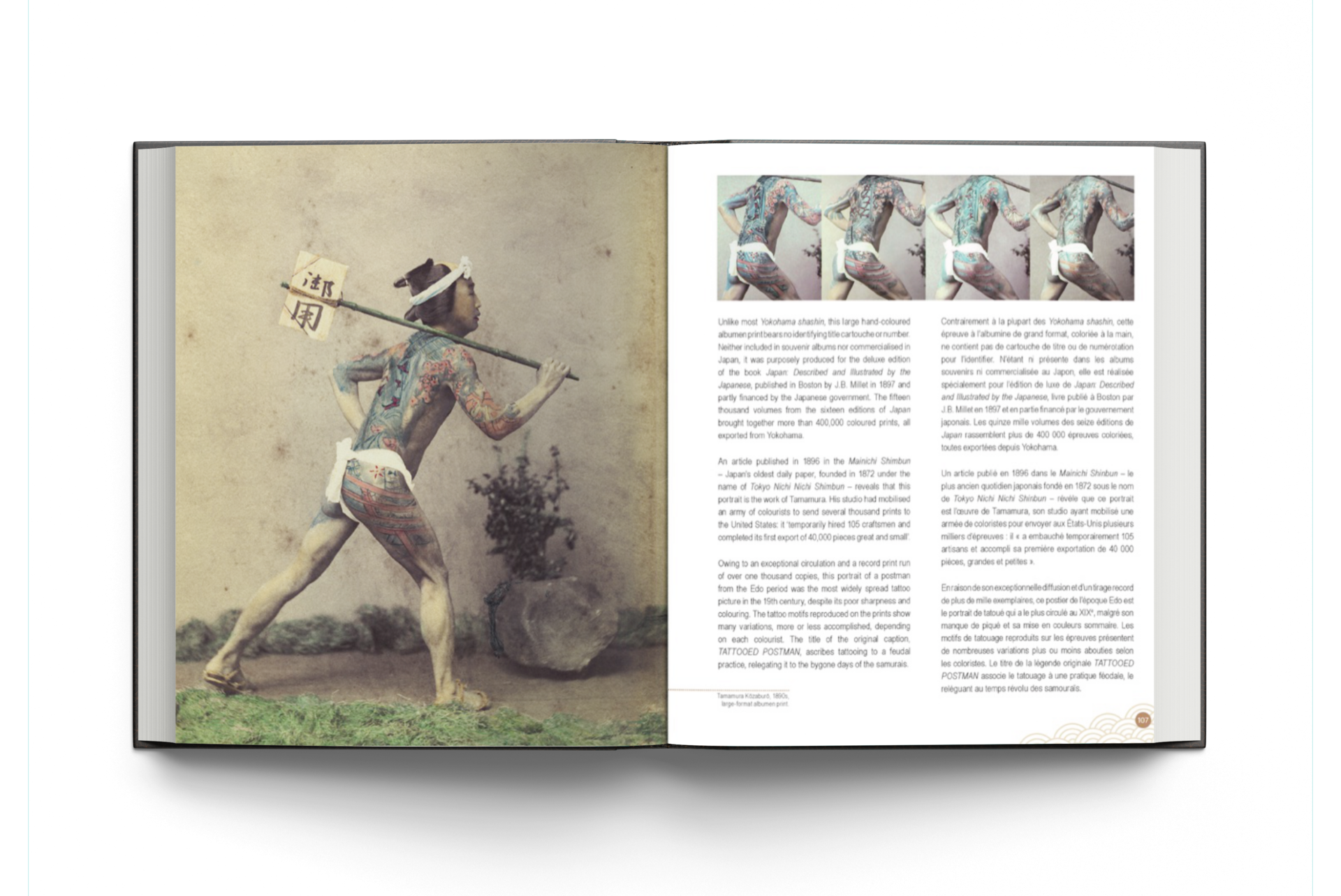

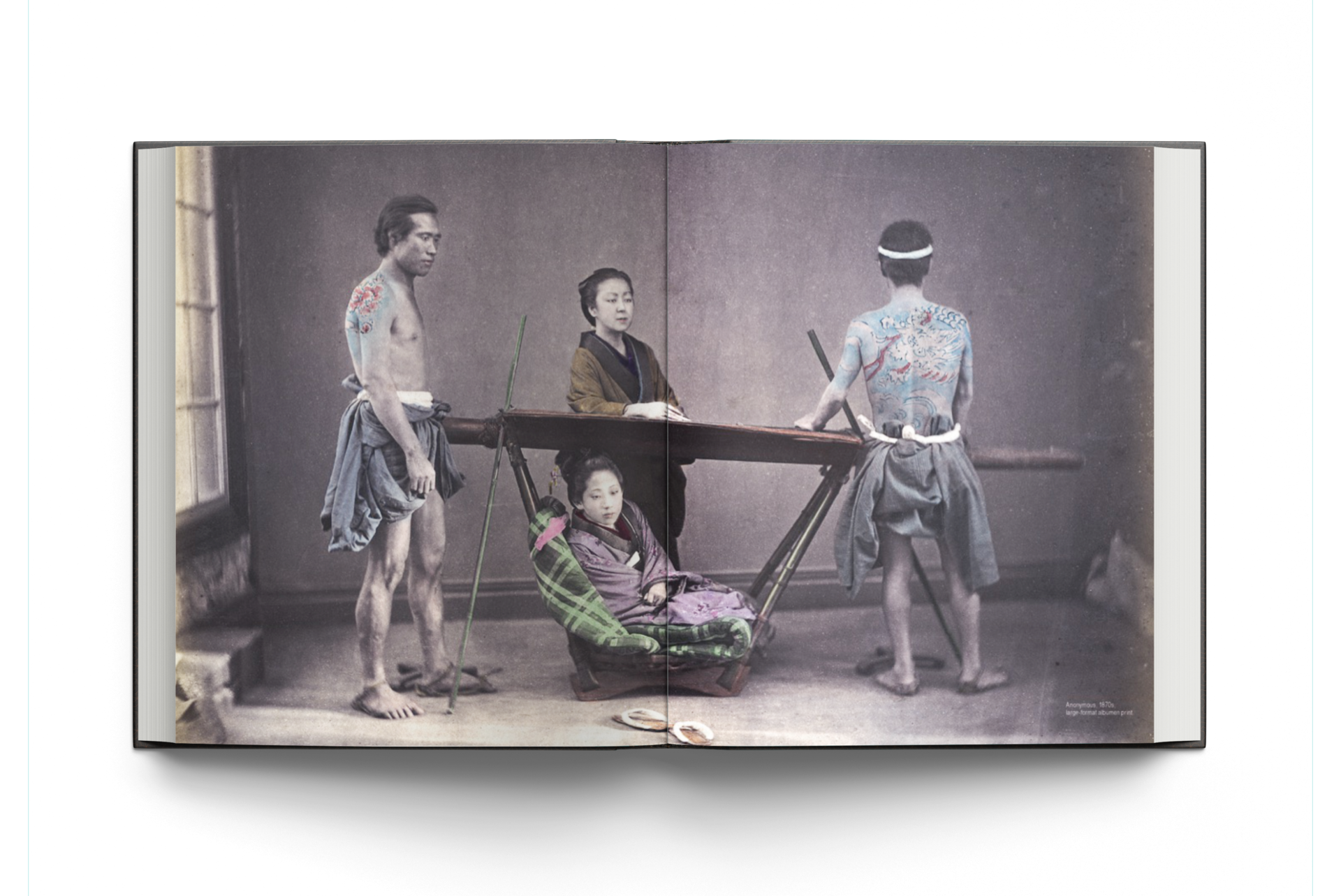

Simultanément, l’engouement des voyageurs pour les clichés mis en couleurs favorise l’émergence de nouveaux ateliers de photographie touristique (Yokohama shashin) qui fleurissent dans les ports commerciaux ouverts aux étrangers. Ainsi, les photographes de renom comme Shimooka Renjō, Felice Beato, le baron Stillfried, Kusakabe Kinbei, Kajima Seibei, proposent tous plusieurs portraits de modèles tatoués dans leurs portfolios.

À cette époque les personnes tatouées, issues des classes populaires, sont majoritairement des hommes, qu’ils soient pompiers, charpentiers, palefreniers, portefaix et autres coursiers. Encore visibles dans l’espace public, ils exhibent leur singularité, ce que le nouveau gouvernement de Meiji leur interdit en 1872 pour satisfaire aux exigences de la morale victorienne.

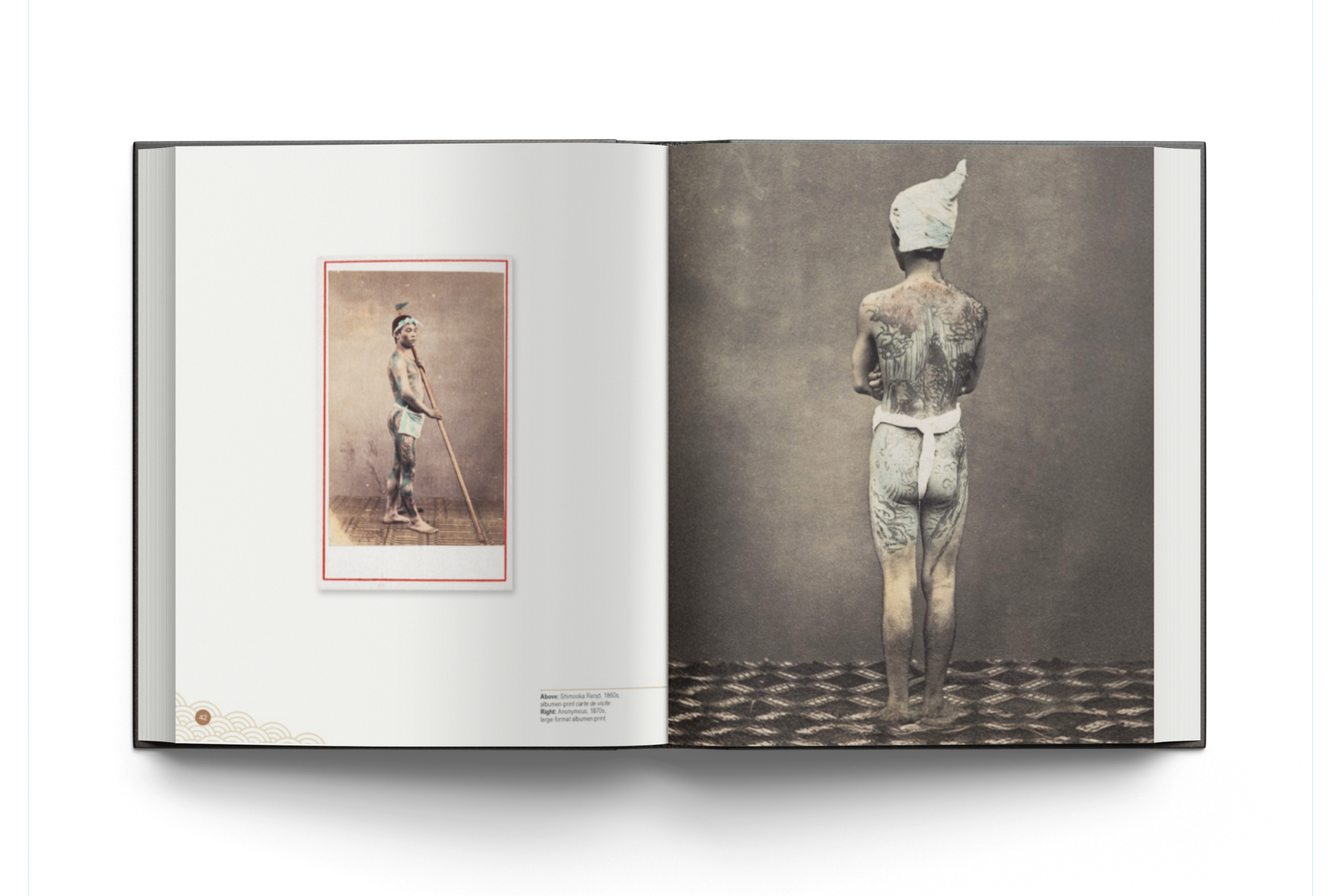

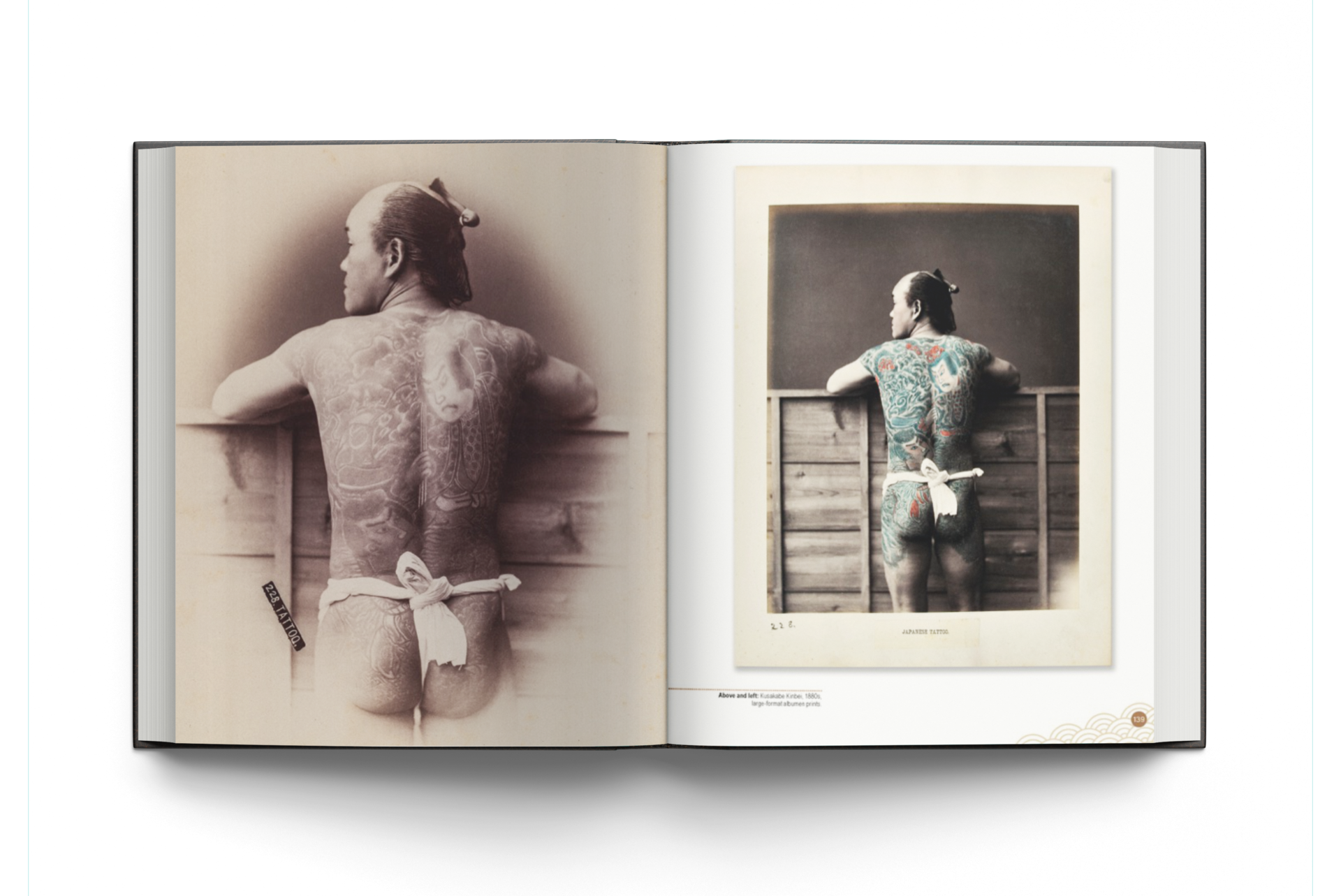

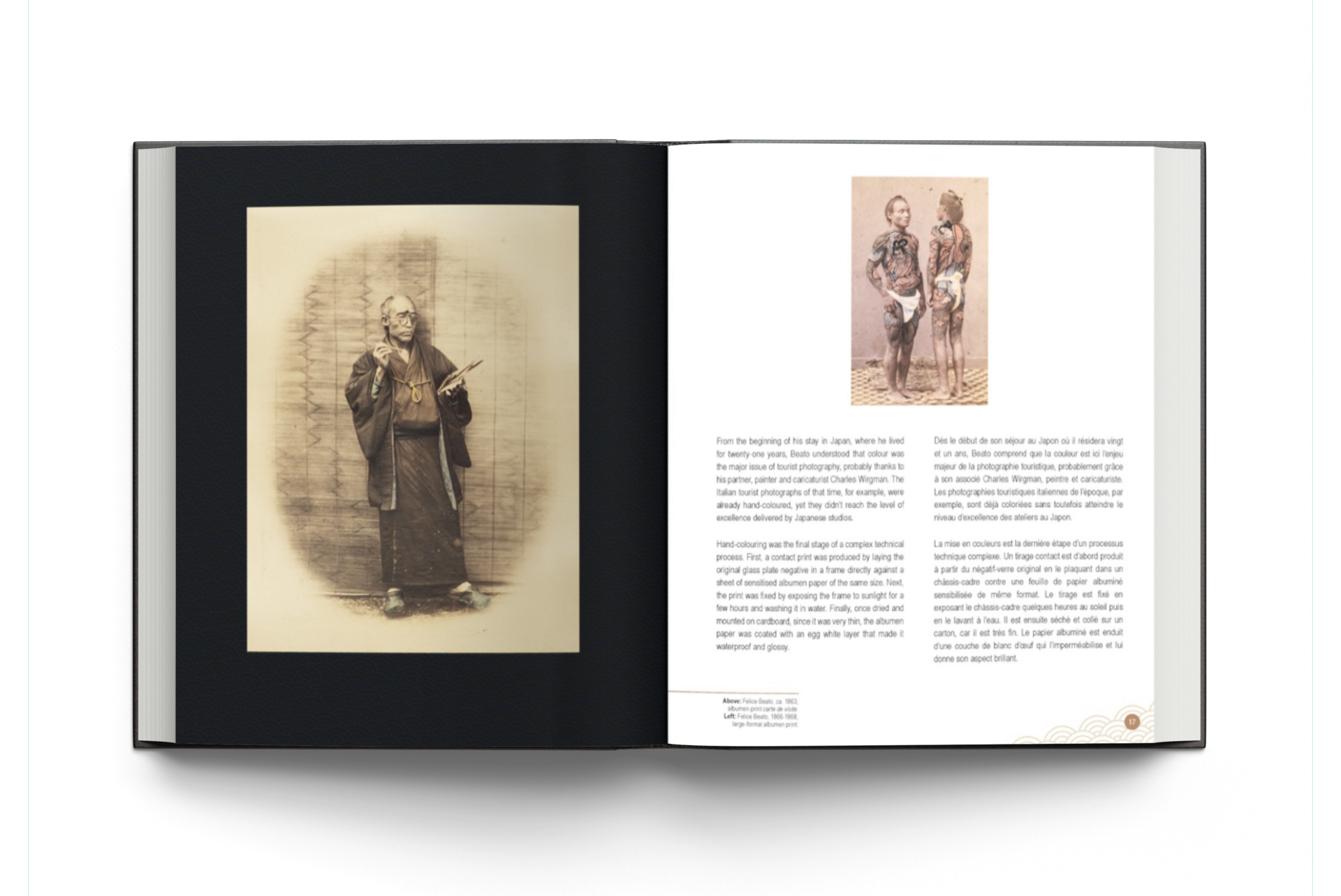

Attestés dès 1859, les tatouages sont à peine visibles compte-tenu du procédé photographique utilisé. En 1863, Felice Beato (1832-1909) et Shimooka Renjō (1823-1914) proposent des portraits de tatoués mis en couleur au format carte de visite. Les tatouages sont minutieusement redessinés, mais la petite taille des épreuves (6 x 9 cm) ne permet pas de discerner les motifs sur lesquels la figure centrale du tatouage émerge. À partir des années 1866, des nouveaux portraits de grande taille apparaissent, un format qui sera habituel pour la photographie touristique produite par les ateliers de Yokohama.

Entre 1850 et 1900, la photographie a pu maintenir une mémoire de l’iconographie du tatouage, alors que celle de l’estampe disparaissait et que l’art du tatouage entrait lui-même dans la prohibition qui ne sera levée qu’en 1948.

The book

It was in 2020 that we decided to pool our skills to undertake this project. We searched the four corners of the world to locate and bring together these forgotten photographs.

Entitled Horimono Shashin, the book will reproduce more than 100 photographs, the majority of which are hand-coloured albumen prints and a few rare magic lantern glass plates. Each image has been restored to bring out as many details as possible of the people tattooed over 150 years ago. The original colours and contrast will be respected (which is often not the case with image banks). The texts will be in English and French, with the English translation entrusted to Didier Mayhew, a Franco-British photographer with a passion for sociology.

The cover will be beautifully finished (softtouch effect and selective varnish) in 21.5 x 26 cm format, and the book will have 192 pages inside on high-quality paper (170 gr.) with headband and bookmark. Printing will take place in October, with dispatch starting in mid-November 2024.

The content

The signing of peace, friendship and trade treaties with the major Western powers in 1858 opened up the archipelago. From the early 1860s onwards, Yokohama became the main trading post for the American, British, Dutch, Russian and French nations, authorised by the shogunal regime. Located close to Edo, which was still closed to foreigners, the port saw the first travellers become enthusiastic about the exoticism that Japan suggested to them at the time, and tattooing was one of them.

At the same time, travellers’ enthusiasm for colour photographs led to the emergence of new tourist photography studios (Yokohama shashin), which flourished in commercial ports open to foreigners. Renowned photographers such as Shimooka Renjō, Felice Beato, Baron Stillfried, Kusakabe Kinbei and Kajima Seibei all included several portraits of tattooed models in their portfolios.

At the time, most tattooed working-class people were men, whether firemen, carpenters, grooms, porters or couriers. Still visible in the public space, they showed off their singularity, which the new Meiji government banned in 1872 to meet the demands of Victorian morality.

Attested as early as 1859, tattoos were barely visible given the photographic process used. In 1863, Felice Beato (1832-1909) and Shimooka Renjō (1823-1914) produced coloured portraits of tattooed people in business card format. The tattoos were meticulously redrawn, but the small size of the prints (6 x 9 cm) made it impossible to discern the patterns in which the central figure of the tattoo emerged. From 1866 onwards, new large portraits appeared, a format that was to become the standard for tourist photography produced by the Yokohama workshops.

Between 1850 and 1900, photography was able to maintain a memory of the iconography of tattooing, while the iconography of prints disappeared and the art of tattooing itself was subject to prohibition, which was not lifted until 1948.

Horimono Shashin

• English and French languages

• En anglais et en français

• Launch of the subscription offer : May 2024

• Pré-commande : mai 2024

• 192 pages

• 22 x 28 cm

• Limited edition and collectors

• Édition limitée et collectors

Contact : horimono.shashin@gmail.com

Téléphone : +33 (0)674 365 916

Xavier Durand

Xavier Durand is a French curator and collector whose field of interest is Japanese culture, mainly japanese prints and photographs. He already curated exhibitions, including « Tatouages du monde flottant » for the museum of Asian Arts of Nice (2023) and « Samurai : art and symbolism of Japan » for the museum of fine arts of Carcassonne (2018). He edited the catalogs of the two exhibitions. He lives in France and travels regularly in Japan.

Commissaire d’exposition spécialiste de l’estampe ukiyo-e et du tatouage au Japon, j’ai été commissaire associé de l’exposition « Samouraï : 1000 ans d’histoire au Japon » (2014), et de « Samouraï : art et symbolisme du Japon » pour le musée des Beaux-Arts de Carcassonne (2018). En 2023, j’ai conçu et réalisé pour le musée des Arts asiatiques à Nice l’exposition « Tatouages du monde flottant« . Je vis en France et voyage régulièrement au Japon.

Claude Estèbe

Claude Estèbe wrote a Phd about Japanese photography in Meiji period (INALCO, 2006). He worked regularly as an expert on Japanese photography for the Guimet museum and the French National Library. He published a few books on Japanese photography including « The last Samurais » (2001) and « Yokohama shashin » (2014). He lives between France and Asia (Thailand and Japan).

Chercheur en histoire visuelle japonaise, j’ai soutenu ma thèse de doctorat sur la photographie à l’époque Meiji (INALCO, 2006). Ancien résident à la Villa Kujoyama, j’ai travaillé comme expert sur les fonds photographiques du musée Guimet, de la BNF et de Meiji daigaku (Tokyo). J’ai aussi publié plusieurs ouvrages sur le sujet dont « Les derniers Samouraïs » (2001) et « Yokohama shashin » (2014). Je vis entre la France et le Japon.

Pour en savoir plus :

- « Tatouages du monde flottant » – Musée des Arts asiatiques – Nice

- « Album de Felice Beato » – Musée Guimet, Paris

- « Samouraï : art et symbolisme du Japon » – Musée des Beaux-Arts de Carcassonne

- « Samouraï : 1000 ans d’histoire au Japon« – Château des Ducs de Bretagne à Nantes

Nous remercions l’aide précieuse de :

- Thierry Causera www.thierrycausera.fr

- Sylvain Durand – photographe infographiste

- Mohamed Ghanem – réalisateur

- Dominique Rodride dominique-rodride.com

- Benoît Varaillon www.uki-ga.com